Question

Please accept my obeisances, all glories to Srila Prabhupada.

Would you be so kind as to give me a guide as to what is appropriate or in which sastra can I find information on what to do when a relative leaves the body?

I thank you in advance.

Answer

This is in no way a complete research and study on Vedic and Vaisnava funerals. Here you find only two articles I found on the Internet, waiting for having more time to write a complete essay or a book.

Actually we have is a very interesting book of 495 pages in our Archive called “Indian Death Rituals” much more sastric than these two articles here. There are quotes from the Vedas, the Upanisads, the Puranas, etc.. Everybody should read that book.

You just have to subscribe to our Archive (www.isvara.org). There are there also several other articles on the topic.

Antyeshti: Funeral Rites

After marriage, most Hindus spend the rest of their lives as householders. After children have left home, there is generally a period of gradual retirement from active life and an increased dedication to spiritual practice. This corresponds to the third stage of life (vanaprastha), which these days is rarely adopted formally and certainly followed less rigorously. A few men still take sannyasa and, leaving home, prepare for inevitable death. In one sense, the whole of life, with its various stages and samskaras, is a preparation for death and beyond.

The funeral rites are almost universally performed and follow similar patterns. Most Hindus cremate their dead.The exceptions are small children and saints, whose bodies are considered pure, and are therefore buried. The rationale is that burning enables the departed soul to abandon attachment for its previous body and move swiftly forward to the next chapter of life. Funeral ceremonies should therefore be performed as soon as possible – by dusk or by dawn, whichever occurs first. Therefore, in India a funeral takes place within hours of death. Regulations elsewhere mean that it may take much longer.

In South India, an annual shraddha ceremony, in which pinda (rice balls) are offered to the Lord and to the departed soul.

There is also a period of mourning, extending to about thirteen days after the funeral (varying according to varna and other considerations). During this time, the family is considered impure. They will not attend religious functions nor eat certain foods (e.g. sweets).

It is a period for giving vent to one’s grief, so that one can live unhindered by unreleased emotions.

Significantly, though, these rites are more for the benefit of the deceased than for the bereaved. They are essential to ensure the smooth passage of the soul to a better level of existence. Most essential is the shraddha ceremony performed on the first anniversary of death. Prasad, often balls of cooked rice, are offered to God and in turn to the departed soul.

The Ceremony

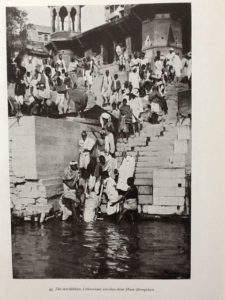

The body is washed by relatives, dressed in fresh cloth, and bedecked with flowers. A few drops of Ganges water are placed in the mouth. The corpse is then carried on a stretcher to the cremation grounds accompanied by kirtan, chanting mantras such as “Ram Nam Satya Hai” (the name of Rama is truth).

The eldest son lights the funeral pyre. For renunciates, it is considered important that the skull is cracked, and this is sometimes part of the ritual, apparently urging the departed soul to move on. Towards the end of the ceremony a priest or relative recites appropriate verses from scripture.

Usually three days later, the eldest son will collect the ashes and place them in the Ganges, or another sacred river. In the UK, relatives may travel to India for this purpose, though some are now using the Thames.

Scriptural Passages

“As a person puts on new garments, giving up old ones, the soul similarly accepts new material bodies, giving up the old and useless ones.”

Bhagavad-gita 2.22

A Vaishnava Funeral – 2

Our Vaishnava funeral ceremonies are in two parts, one at the house for those taking part in the traditional rites, and the other at the crematorium which is also attended by other friends and distant family.

Antyeshti-karma, or the funeral rites, involve songs and prayers before the open coffin, along with expressions of appreciation for the devotee’s spiritual life.

Sacred objects such as garlands, tulasi wood, dust from Vrindavan and water from the Ganges river are all placed upon the deceased.

A last arati is offered to the home altar and all the mourners place flower petals at the feet.

Prayers to the Lord are then offered on behalf of the departed Vaishnava and the cremation process ceremonially begins by the chief mourner offering grains of barley and sesame seeds mixed with ghee into a flame.

The assembled devotees then all sing a final kirtan, offer their respects to the departed, and the coffin is then closed.

At the crematorium we again reflect on how the departed devotee contributed to our own life, and how they offered us inspiration by their fine example.

There is then a reflection upon how transitory the body is compared to the eternality of the soul.

Normally this is accompanied by scriptural readings, often from the second chapter of the Bhagavad-gita.

Finally, relatives should come forward and place their hands upon the coffin as we all – perhaps one hundred devotees in all – stood to recite the last verses of the Sri Isopanishad:

“Now let this body be burned to ashes…”

Then the coffin slowly disappeared behind the curtains.

Afterwards, after we had consigned the coffin to the flames, I took the family members through a short tarpana ceremony, an offering of water on behalf of the soul, and then everyone lined up to offer them condolences.

Leave a Reply